-

March of Fire

Volume One of Rattle Their Bones

“If after death your body kept its shape,

we might hope it will be revived again,

Just as a jug, emptied of wine, could be refilled, as long as it remains unbroken.

But all its parts have come undone and

turned to particles of dust, swept away by the winds.”

Abu al-Alaa al-Ma’arri

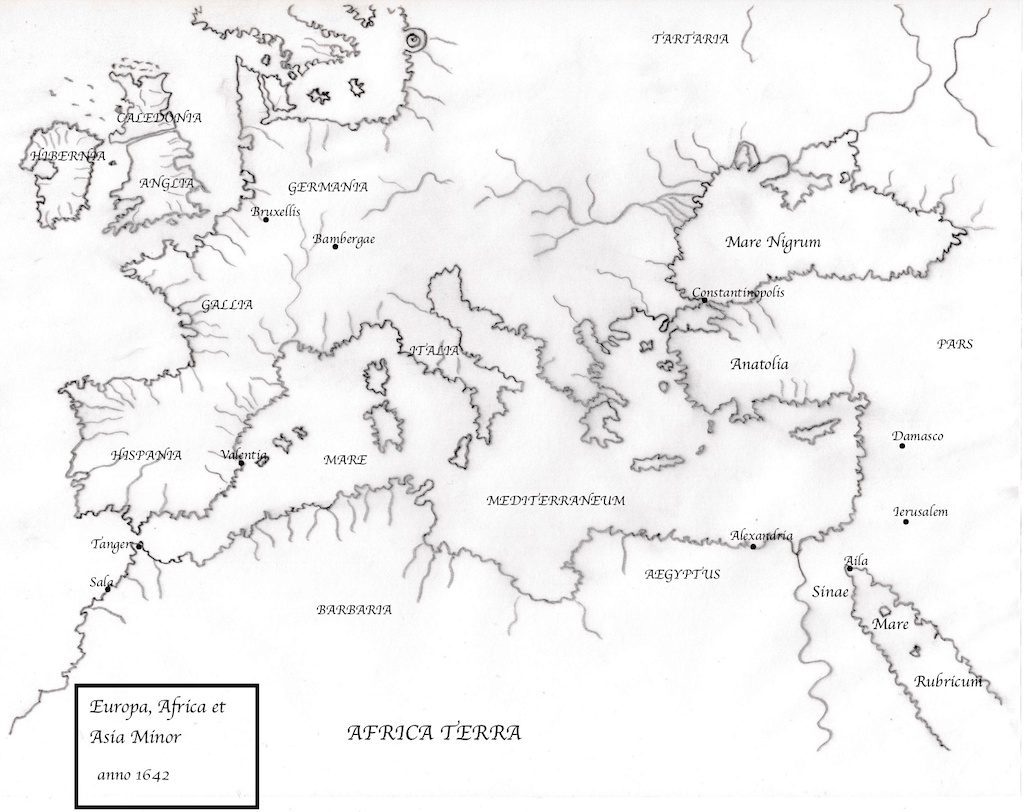

England, 1628. The bloody war of religion in Europe continues, and after a botched and bloody defeat by the French, King Charles I’s most trusted confidant and military commander, George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, is murdered in Portsmouth in broad daylight. The assailant is a grieving and vengeful soldier, Jack Felton. The King is convinced that the murder of his closest ally is a conspiracy by Parliament, but his advisor, William Laud, Bishop of London, who has his own political ambitions, convinces King Charles I that dark forces greater than Parliament are at play. Laud points the finger at Scotland, where witchcraft is rife.

As King Charles I comes to terms with the loss of the Duke of Buckingham, William Douglas, the Earl of Morton, a staunch Royalist, is desperate to gain favour with the King by raising money to fund the King’s hitherto failed wars. But to do so, he must secure the inheritance of his half-sister, Lady Margaret Douglas, the cousin of John Lyon, Lord Glamis, who has given her refuge at Glamis Castle. Margaret soon finds herself battling her half-brother to keep her rightful inheritance, but amid murder and treachery at Glamis, and the desperation to conceal her illegitimate daughter, she is wrongly accused of witchcraft, and of conspiring with Jack Felton to murder the Duke of Buckingham. As Margaret’s fate is determined, the rift between those Scots loyal to Scotland and its religion, and those swearing fealty to the English King and the new faith, deepens. But all is not what it seems….

Thirteen years later, in 1641, in the Lands of the Ottomans, a former soldier is sent on a mission to a monastery in the Sinai desert to recover an ancient deed that could determine the outcome of the war in Europe. When a murder is committed, and the deed is stolen, the race is on to recover it. Should it fall into the wrong hands, the fate of Europe- and lands far beyond- hangs in the balance. It soon becomes apparent that Margaret’s fate thirteen years earlier, this deed, and the soldier tasked to recover it, are closely connected, and that the survival or fall of kingdoms rests with those who, above all, wish to right terrible wrong.

March of Fire

Chapter One

He rode, hard and fast, through the howling wind and driving snow, thundering hooves beneath him beating away the time, time he could not afford to lose. Through the thicket he saw the forest clear to the open fields of the Pentlands, and beyond, the granite spectre of the city appeared, the castle on the hill emerging in the frosty mist: Edinburgh. He could almost hear the tap-tap-tap of the slow death drums as the procession would be pushing her towards the waiting fire, throngs of people jostling and heckling the executioner and the condemned, a trepid anticipation for most, and a gleeful sight for the more deranged: the burning of a witch.

We must make it in time, Dealanaich, the rider urged his mount on, with his heart almost in his throat at the prospect of failing in his mission, we must make it before it is too late…

But time, as was her habit, would wait for no one; and the gut-wrenching stench of burnt flesh and the horrific spectacle of cindering bones assaulted him with every sharp gust of wind when he, Jack Lyon, pulled up his steed at Castlehill, the last, and now a lone, witness of her burning. Utterly disbelieving, his heart torn, he stared at the smouldering pyre, ash and cinders all that remained, save a few charred bones and teeth that peeked through the smoke and lingered in the last of the glowing embers.

So absorbed in his failure, and his grief, was he, that the sound of a voice behind him echoed only distantly in his mind, until Dealanaich, who recognized the stranger’s voice, whinnied softly and nudged her master back to the world of the living.

“My Lord,” the young voice repeated, “I am so glad you have come!”

The boy could almost not recognize his master when he turned to face him; the confidence and courage he remembered of Jack Lyon, Lord Glamis, now gone, instead before him a broken man, bloodshot eyes, pale as death and body so beaten with worry and exhaustion he would have fallen to the ground had the boy not caught him first.

“My Lord!” the boy said again, anguished at the sight, but Lord Glamis brushed him off dismissively, too ashamed to face the boy.

“Aye, I came, Hamish, but too late,” he almost sobbed.

“Aye, sire,” acknowledged Hamish, “but you’d not have been able to stop them- the forces were so strong against her!”

They stood silently for a while; above, a buzzard and a crow circled and spun, one around the other, taunting each other, competing for their prey somewhere below. It seemed like night, but it was only late afternoon; the sun still lingered some way above the horizon, peering through the clouds, and in the distance, the cacophony of sounds and overwhelming smells of the market crowds slipped in, between the smoke and the low, slow gasps of crackling embers and dying flames.

Hamish paused for a moment, considering his words somewhat first, before he broke the silence.

“My Lord, I never saw a lady with such courage in an hour of such darkness; she neither flinched nor cried as the flames took her! She spoke, until she could not speak anymore- she cursed them all, my Lord! The King, the Bishop, the General…. and even her brother!”

Lord Glamis felt a sharp jolt in his heart.

“She was alive, Hamish? Alive, when they lit the fire?”

The boy replied with a barely noticeable nod; it had been an ordeal so horrific to witness it was beyond imagination, beyond description.

“No poison first, Hamish?” persisted Lord Glamis, his voice trembling, “no long, cold, iron grip around her neck to hurry her death before the flames consumed her?”

“Aye, my Lord, she was alive,” were all the words Hamish could find to reply. He knew his master well; and he knew his anger was beginning to fill the hollow grief he felt. And the young lad was not wrong, for Lord Glamis began to feel the hatred, and thirst for vengeance, flood his senses.

William Douglas…. Lord Glamis thought and bitterly cursed the man responsible, even if it drains the last drop of my blood, I promise, you will pay dearly for this! I shall have my pound of flesh and you will rue the day you dared to anger the House of Glamis!

Images of her in a sea of flames flashed into his dark thoughts, and the grief returned, when he suddenly remembered: what of his niece?

“Balgaire,” his voice, now frantic, shook slightly, terrible thoughts of the little girl’s fate entering his mind, “where is my niece, Hamish? And why did McAdam and Alastair not come with you?”

“I beg pardon, my Lord,” his servant answered carefully and cautiously, “I thought she had told you! McAdam took Balgaire to safety…. they sailed to Germany, to stay with your cousin, Robert Douglas!”

Hamish waited to continue, hoping his master too distracted to pursue his inquiry about Alastair; but Lord Glamis, although he was plunged into sorrow, and so consumed by guilt and hatred, was gathering his reason, and insisted so strongly that the poor boy had no choice but to answer.

“And Hamish,” he asked again, now looking directly with piercing bloodshot eyes at the boy, a hardness from his master the young lad had not felt before, “where is my steward, Alastair?”

The snow had eased, and the clouds gave way to the orange glow of the late afternoon sun, the wet and cold cobblestones glistening a bright russet as the light struck the streets; they seemed cleansed, renewed.

“Master Alastair…pardon, sir, I thought you knew!”

“Knew what, Hamish? Has something happened to him?”

“I dunno know, my Lord…. but, er, we cannot find him anywhere after all the murders! The sheriff is searching for him as we speak!”

Alastair, thought Lord Glamis, you fool, what have you done this time?

He looked past Hamish towards the city; everything was as it always had been, the burning of innocents as common and routine now as the bloody spectacle of a cockfight and it truly horrified him. He turned his gaze towards the dying fire once again.

“Gather the bone and ash, Hamish, or what remnants of those you can,” Lord Glamis muttered. The snow had begun to fall again, thick tufts of white descending gently onto the pile of ash and bone before him, dampening the last few breaths of the fire. “The embers are almost cold.”

“Yes, my Lord,” nodded Hamish, and not feeling his question impertinent, he asked, “but who will bury her, my Lord, as a witch?”

There were few who would bury a woman condemned to the fire for witchcraft, even those of higher birth did not escape the curse of superstition that came with such an association.

“I will bury her, Hamish; she will return to Glamis and rest there, where she belongs.”

The young lad, himself weary of the constant flavour of death he had been forced to taste in recent weeks, scavenged the bones and ashes, and amidst the debris, he found a jewel; it was a ring.

“My Lord, did this belong to her?” he held it out in his bony, blackened hands, carefully shaking the ashes away; his master took it from him, curious.

“Aye,” he smiled, for the first time in a long while, “aye, a gift from me; it belonged to my mother.”

It was not lavish, but beautiful, nonetheless: a thin, gold band carved with flowers and leaves, and inscribed on the inside were only two words: salus mea- my salvation.

“I will keep it with me for now,” he decided, and slipped it into his mantle pocket; the wind was picking up, and the light was beginning to fade.

“Let us be rid of this godless place, Hamish; we have a long ride home.”

“Aye, my Lord; but you have come far today already: do you not wish to rest here in Edinburgh, and continue tomorrow, instead?”

“No!” Jack Lyon snapped at Hamish so sharply, the boy jumped a little. The thought of remaining in the city that took her away too much for the wounded heart of Lord Glamis to bear. “If I never see this city again, Hamish, it will be too soon!”

Her ashes and bones by his side, wrapped in a cloth in his satchel, he and the young lad began their journey home. They passed through Newgate, along the markets, at one point almost unaware of straying missiles in the form of rotten apples assailing them, turning to see another weary stranger and his horse contending with a rabble of child vagrants, before they passed through the city gate and found the road to Glamis. Hamish and his master were both exhausted, the horses weary, and so the journey was slow. They did not reach Glamis until after midnight, the dim light of the waning crescent moon fading with the last hours of Allhallows Eve, the Day of the Dead.

Into your hands, O merciful Saviour, we commend our sister, Margaret.

Acknowledge, we humbly beseech you,

A sheep of your own fold, A lamb of your own flock,

A sinner of your own redeeming.

Receive her into the arms of your mercy,

Into the blessed rest of everlasting peace,

And into the glorious company of the saints in light. Amen.

*

The City of Portsmouth, England, about two months earlier, on August 23rd, 1628

“Villain!” he screamed, spluttering, stumbling, awkward and dis- believing into the crowd, as if he had encountered the Devil, a flood of crimson seeping through his torn shirt, and he, George Villiers, the 1st Duke of Buckingham, trying in vain to pursue his killer; but he fell down dead, on the cobbled stones outside the Greyhound Inn, and the gathered crowd cheered at the death of the King’s favourite.

“The Duke is dead, and we are rid of strife

By Felton’s hand that took away his life!”

The hero, for so he was to almost everyone who had witnessed the assassination, was Felton, and he, barely interested in an escape but more in knowing that his final mission had been accomplished, was able to flee down only a few of Portsmouth’s streets, until the King’s guards tracked him down. He knew he would die in prison, or worse, but that was irrelevant. Felton had achieved what he set out to do- and brought justice to all the soldiers who had died under the careless protection of the villain Villiers; he knew the resounding infamy of his crime would live beyond his death, and that, to Felton, was all that mattered.

*

Southwick Park, St Mary’s Priory, Portsmouth, the same afternoon

In a spacious chamber fit for kings two men appeared to lan- guish in its sombreness; one was in repose on a comfortable bed, for he was, in fact, the King. It was not, at that moment, a place of lighthearted discussion; neither the dark curtains, filtering out the intermittent light from the sun, nor the teal stone walls with the somber-faced oil paintings encouraged a feeling of hope or happi- ness. The stern demeanor of Archbishop Thomas Cromwell and smug imperiousness of King Henry VIII, both ardent dissolutionists, had been left as a final insult to what remained of the Priory after King Henry’s act of vengeance against the Church.

“My soul-mate,” began the King, hesitating, and drawing in a wounded breath, “the most devoted friend to this Crown..is dead….,” he moaned, “dead!”

He, King Charles I of England, Scotland and Ireland, was not usually one of such naked sentiment, and threw himself back onto his bed; he had barely ventured from his chamber since the news of the Duke of Buckingham’s death.

His head half buried in the goose down blanket, he turned a little to look at the only other person in the room. William Laud, the Bishop of London, was about to speak, but the King paid no attention.

“Murdered by one of our own. Murdered!” he shrieked; grief had taken over his senses, it pierced his skin, cut his flesh, and gnawed at his bones without mercy. He was unable to form rational thoughts in his mind; oh, how he wanted his dear, dear, handsome friend, in- stead of this ugly, pompous figure standing condescendingly before him, forgetting for a moment the true loyalty the Bishop had always offered the young King, and his father before him.

A tear formed in the corner of the young monarch’s pale brown eyes, collecting momentum before it rolled reluctantly down his cheeks, blending unobtrusively with the saliva and mucus trickling from his nose, and clinging on to his thin moustache. The Bishop could only look away; he, too, was deeply grieved by the death of one of his own favourites. But, he was the Bishop of London, and must hold his composure, and banish thoughts of the flesh- at least when he was in the company of those whose favour he wished to uphold in order to advance his own ambitions.

Apart from the faint tapping of a wind that had picked up against the windows, there was a hollow silence. Neither of them moved. One was too grief stricken, his mind appearing to have temporarily left his body to find some relief in another dimension; the other was too uncomfortable and apprehensive to be seen as weak, and thus, for him to offer any gesture of comfort, or words of solace, were not an option.

It was late afternoon, and the daylight began to fade across the skies. Beyond the fields and gardens of St Mary’s Priory- or, what was left of it- that were visible through the windows, the light of the on-setting evening crept across the sea, the first shadows closing in on the silhouettes of the naked trees and woods, cloud-shaped forms of grey sweeping over the water with the late summer winds. Only the last glowing embers in the enormous fireplace of the King’s chamber offered light and warmth in an otherwise bleak moment. It was the loud crack from the wood yielding under the heat of the fire that forced the King to rouse himself. He cleared his throat, and, removing himself from the warming comfort of his pillow, he turned to the window. His own reflection horrified him, and while attempting to tidy long curly strands of dark hair, he asked:

“And what have you to say of this…. utterly heinous business, William Laud, as Bishop of London, keeper of the faith?” the King suddenly had found interest in his fellow chamber mate, or perhaps he was tired of feeling like he was talking only to himself, or God, who appeared not presently to be inclined to listen.

The fire in the hearth had begun to diminish, and the chill of the late summer clung to the great, thick stone walls of the Hall. The Bishop felt the slight cold, too, and tended to the glimmering logs, pushing them about to stir the flames, as if they would perhaps offer some answers or arguments for the King.

William Laud was a tall and intimidating figure, eyes and brows permanently raised in a look of haughty suspicion, even more so as he stood, feet firmly apart, in his long, blue bishop’s cloak, with the high and stiff white frilled collar, and the flat black cap. The gilt and yellow tunic and black trousers he wore made him, in his opulent presence, all the stuff that archbishops were expected to be made of, at least in his own opinion, and he now formulated in his clever head an answer to the King’s question, which he, the Bishop of London, hoped would help his own cause for advancement, feeling himself the only cleric worthy of becoming the next Archbishop of Canterbury.

“Your Majesty, I am at a loss for words,” he began, very well aware that he was in fact rarely in such a situation, stroking his thin grey tuft of a beard, “the Duke…” he stopped briefly, composing himself again as he thought of that beautiful figure of a man, now pale and dead and utterly lifeless, whose soft touch and mellow voice had been sent to the vast eternity above, and was now beyond his reach forever, “was a man of state, of greatness, and his murder is a crime so vile, those responsible will feel the violent wrath of the law, of this I may assure you!”

It was not Laud’s own voice, raised and shaking in anger and grief, that had surprised the King, who had only half-listened, some- what distracted; rather, only two words the Bishop had spoken had caught hold of him, and, becoming inquisitorial, he turned a sharp tongue to the Bishop.

“Those responsible?” he asked, releasing himself from the com- forting softness of his bed, his red-rimmed eyes almost matching the deep red of the velvet curtains that surrounded his four-poster bed, which, in the vastness of his chamber, seemed quite small, almost ridiculously so for the grand status of a King of three countries.

He left his bed and moved closer to the Bishop, who had not flinched from his resolute stance by the fireplace.

“Do you mean to tell me, Bishop, that Felton, curse him!- did not act alone?” he pressed for an answer, clenching his fists, deep grooves furrowing his pale brow as all manner of dark thoughts entered his disturbed mind.

The Bishop was once again too slow in replying, while the King continued his rant, a mixture of deep wounded sorrow and fiery anger, barely able to keep control of his reasoning.

“The Spanish- a curse on them, too!- they always despised George, after the business with the Infanta Maria- which was the fault of their blundering, not my dear, most excellent George! And now that we are at war with them, they would do anything to destroy my image- anything!” He paused, a darkness coming over his pale, worn face, eyes narrowed and lips pursed as his resentment grew ever deeper.

“Philip and his so-called Prime Minister, that oaf of a man Oli- vares, have never shied away from committing the foulest of crimes to save their pathetic empire from further ruin!”

Laud, who had in exasperation tried to intervene on several occasions, could, to his extreme irritation, not find a gap in the King’s tirade in which he could successfully interject his opinion, which in his own humble opinion, was in fact much more important, and actually far more interesting, as the King, now thoroughly worked up, spilled his mind’s contents to the chamber.

“Or Richelieu- that blaggard! He, who calls himself a Cardinal, a Man of God, interlocutor of higher wisdom- hah! He would sooner see George dead than anyone else, even sooner than Philip, after the treacheries of the Isle-De-Re and La Rochelle!”

Seizing a vital second of silence, the Bishop, who had in his mind moved swiftly onwards with his self-serving plan while the King had moaned, replied forcefully:

“Majesty,” he flattered, “although I cannot deny the shrewdness of your interpretations of the political treachery of our foreign enemies, I fear the treachery is rather more close to the heart of your own Crown lands…. you may have heard that there is talk that the Devil’s work is afoot in Scotland?” He paced deliberately slowly back and forth in front of the fireplace, the flickering flames light- ing up the one side of his face; he looked, thought the King, rather ridiculous, reminding him of a court jester he had once imprisoned for mocking his mother.

“Scotland? The Devil?” the King asked, confused and irritated; he had never had much time for the Scots, his almost complete lack of interest in that place, save the country’s questionable stance on religion, preventing him from visiting his birthplace since his father’s accession to the English crown had moved them all south of those borders.

“Scotland?” he said again, with great vexation, wondering what other political maneuverings he had failed to see in the recent calamities that had befallen his kingdom.

“Yes, Majesty, Scotland- unfortunately, in addition to the usual troubles we are faced with in that heathen-filled place- although the border reiving has mostly come to an end, thank the Lord,” he crossed himself theatrically, “more recently, there have been discoveries of witches- powerful witches, who do the Devil’s work with great cunning and deceit!”

The King was disappointed. He had hoped there were some more rational and intriguing explanations, to do with matters of higher state and complex politics, that could have appeased his conscience; unlike his father, he had no great belief in the ability of witches, and how, even if there was some connection, would witches in Scotland have anything to do with the assassin Felton, an English soldier, or his dear, beloved, dead friend?

“Witches, Bishop?” he murmured, deflated. “Does that not seem unlikely? What is your evidence for this?”

Laud had been accustomed to the frequent obsessions with witches and witchcraft of James I & VI, the King’s father, whose own work on the subject, Daemonologie, had been published a few years earlier; the Bishop therefore found Charles’ lack of interest, which almost reached the extreme opposite of his father’s unrelenting passion, unsettling, and replied with an attempt at patience:

“Sire, witchcraft is not a matter to be trifled with; and we do have evidence that a witch in Scotland- one of noble birth, at that! had influence in the death of the Duke of Buckingham, God rest his precious soul!” He crossed himself again, and continued quickly:

“This lady of noble birth had been under suspicion from her half-brother, the 7th Earl of Morton, William Douglas, for some time; and he has himself witnessed her deceit and sorcery. It may inter- est you, Majesty, that the Earl of Morton’s own son is married to a niece of our dear, departed friend, the Duke of Buckingham…. so you see, the familial connections are strong.”

This new information was beginning to take a hold of the King’s interest, but he was not wholly convinced.

“But why, Bishop?” Charles, still unconvinced, attempted to paint a picture in his mind of the situation, but all that entered into his mental visions was an angry and bitter old crone, who for whatever reason was sitting in her rocking chair in a remote half- ruined castle in Scotland, casting spells over a brewing cauldron and muttering curses on George. He had heard his father speak of the subject often, and had been forced to read his work, and al- though it had been thoroughly studied, Charles had never believed as fervently as his father of the influences of witches; to the cur- rent King, a witch seemed to be nothing more than an aggrieved old woman who had upset her family or fellow parishioners about some small trifling matter; they, in turn, wanted their revenge, or to get their hands on some part of her fortune.

Knowing he could not provide a satisfactory answer to the King’s rational question, Laud replied in an overly sinister manner:

“Witches need no other reason, my Lord, than the uncontrollable desire to practice that dark magic to satisfy the whims of their master, the Devil.”

“Hmm,” grunted Charles; he had hoped for a more sensational political argument, one which he could use to punish Parliament, which was an increasingly sharper thorn in the King’s side as the days went by. Try as he might, he could not muster up the enthusiasm for the sinister idea of the witch, even less so in connection with the death of his friend.

“And who is this lady you speak of?”

He had moved to the window again; the rain had started to fall, small drops sliding rhythmically down the glass, blurring the shapes of the trees and hills below him in the distance, and blending with the vast iron-grey sea beyond.

“Lady Margaret Douglas, my Lord; she is a Douglas, for whom your grandfather had great enmity- their treasonous past is well- known to the Stuarts.”

Charles frowned, dismissively waving a hand to an unknown recipient.

“Her brother is also a Douglas- why should he be less treasonous? How do we know that he does not have some selfish interest in persecuting his sister, Bishop? It sounds nothing more to me than a trifling family squabble!”

The King remained hopeful that a treacherous Parliamentarian plot was behind the death of George, and that Felton was merely a small pawn in a vast political conspiracy that sought to bring about his own downfall; for he knew that such a conspiracy was real and ever present.

The Bishop replied soothingly, as if speaking to a small child: “Sire, the Earl of Morton is the right sort of Douglas; he has only ever been a loyal supporter of the Crown, and yourself, I assure you! His only interest is to serve and protect you, and the future of the Stuart line.”

Thunder rolled in the distorted hills beyond, an invisible assail- ant from the skies, and her inevitable companion, lightning, flashed in thin irregular streaks across the teal clouds. Tears from Heaven, thought the King, lamenting the death of his trusted friend, rage from God against the evil that has beset my own household. Evil; the work of the Devil.

Feeling the King still lacked conviction in his explanation, the Bishop continued:

“Her mother, you may have heard from your own father, was Jean Lyon, Countess of Angus, herself daughter of the 8th Lord Glamis; she was also accused of witchcraft by your own great father. Furthermore, the 8th Lord Glamis was the grandson of Janet Douglas, Lady Glamis, burned at the stake for witchcraft by your own great-grandfather, King James V….. so you see, my Lord, the history of Douglas treachery along the female line against the Stuarts is a long and deeply rooted one; and one which I, as Bishop of London, and your spiritual and political advisor, would implore you not to ignore!”

The embers in the fireplace began to burn down, and Laud, being tired of having the task of stoking the fire, rang a bell, after which a young and nervous-looking steward swiftly appeared to tend to it. He reminded the King of George- dear, beloved George!- tall, and dark, and lean and charming. He could not help but stare at the boy, who in reality had no resemblance to the Duke at all, save perhaps his noticeable height, and the boy, conscious of eyes burning into his back, he hurried his task, and once finished, bowed deeply out of the door, and hoped he would not have to return again soon. Once the boy had left, Charles, saddened, considered a short while, and asked, half-mocking:

“And, Bishop Laud, if the tragic death of my dear, dear friend is indeed a plot by the Devil, what plans do you have to deal with the matter?”

Pleased that he had finally gotten through to the confused muddle of thoughts in the King’s head, Laud replied confidently:

“I have two men in mind, sire; one is an expert, a witchfinder general by the name of Matthew Hopkins with a most stellar reputation for successfully prosecuting a large number of witches here in England, and he is one of my most ardent followers. The other is a priest…a Catholic from Spain…”, but before he could finish Charles threw him a suspicious glance and interrupted.

“A Spaniard? We are now to trust the treacherous Spanish?” “He is the Head of the Order of Christ, and well-practiced in the Inquisition,” the Bishop reassured, “his loyalty lies with the Catholic faith, and not with the Spanish King. I would keep his name and presence a secret for now, though, but I have asked them both to await my instructions- with your permission, I will dispatch them to Scotland immediately to deal with the matter. The Earl of Morton knows of Master Hopkins and his work, and is eager to be of aid in bringing an end to the Devil’s work, now so rampant in Scotland!”

“Even if this means bringing about the end of his own flesh and blood?” inquired Charles, astonished that even a half-sibling would wish the death of a child of one of his parents.

The weather had now taken a turn for the worse, the lightning and thunder raging violently, rain lashing hard against the window, a stark contrast to the calm and quiet of the King’s chamber. God’s wrath, he thought; He is asking for vengeance, vengeance for my friend.

Charles moved away from the window to face the Bishop; the two men were about the same height, tall in stature, but where Charles’ slender and slight frame belied the hardness of his ambitions, Laud’s big and broad form hid well the delicate feelings he harboured towards men in particular, and he, to an outside observer, would have appeared to be the dominant stronger man, a physical symbol of masculine might and power, as the fixed norms of social perceptions had required.

Sighing reluctantly, but exhausted at the thought of who his friend’s band of assassins might include, the King nodded feebly.

“Very well, Laud, if you think this will avenge George- do what you believe you must do. But involve me no further with the proceedings until you have reached a verdict- or if you discover a wider conspiracy against me, as I know there must be behind this horrible business! And keep an eye on the Spaniard- I will hold you personally responsible if he betrays us!”

He waved a dismissive hand at the Bishop, who bowed deeply as he backed away to the door.

As soon as the large oak doors had shut, the King could do nothing but succumb to intense grief and began to weep again. His soul- mate, his friend, his rock and mountain, lay dead in the morgue, cold and statuesque, and there was nothing he could do to bring him back.

But he could take back his pound of flesh; and he swore to himself, if it was the last act he would perform on earth, that he would make those who murdered his most ardent confidant and beloved companion pay for what they had done- blood for blood, he thought, as anger and sorrow strangled his bleeding, suffering heart.

Subscribe

Enter your email below to receive updates.